You don't need Slack. You need slack.

Summary

To get the most of yourself and your team, you need more of the common noun - “slack”; i.e the time or resources you hold in reserve. Having slack is counterintuitive, but it can benefit you in a few ways.

Avoid the trap of being too busy to improve.

Create the mental space to recognise problems.

Step back and examine your work in context of your long term goals.

Pause so your brain can forge connections between existing elements and arrive at new ideas.

Operate at 85% capacity, so you can achieve elite performance by harnessing your subconscious mind.

The trouble with popular applications named after common words, is that they appropriate the dictionary word. Take Slack, for example. Most people associate the word with the IM application they use at work. But slack; note the change in case; can be a powerful tool for change and improved productivity. Unlike of course, Slack, which when we misuse it, can be a major distraction.

Of course, the dictionary definition of slack isn’t complimentary. Oxford languages provides one definition that relates to what I’m about to share with you.

“A spell of inactivity or laziness.”

That definition is indeed part of the problem. We often equate inactivity with laziness. Even in my personal life, I tempt myself to fill every waking hour with what I consider to be productive activity. If you’re doing nothing, are you really utilising yourself? Turns out, yes - you need unplanned space where you do nothing, to get better at the things that you enjoy doing.

This is where I like the notion of slack, that Dan Heath describes in his book - Upstream.

“Slack, in this context, means a reserve of time or resources that you can spend on problem solving.”

So in today’s post, which incidentally is the first for the year, I want to tell you why you must cut yourself and your team, some slack this year.

Don’t be too busy to improve

As a consultant, I’ve often had to help teams improve their ways of working. Everyone usually means well. Everyone wants to improve. Except there’s one problem. No one wants a hit on productivity. On many software projects, the measure of productivity is also a single dimension - velocity. But that’s beside the point. The bottom-line is that we all want to improve, but we don’t want to slow down.

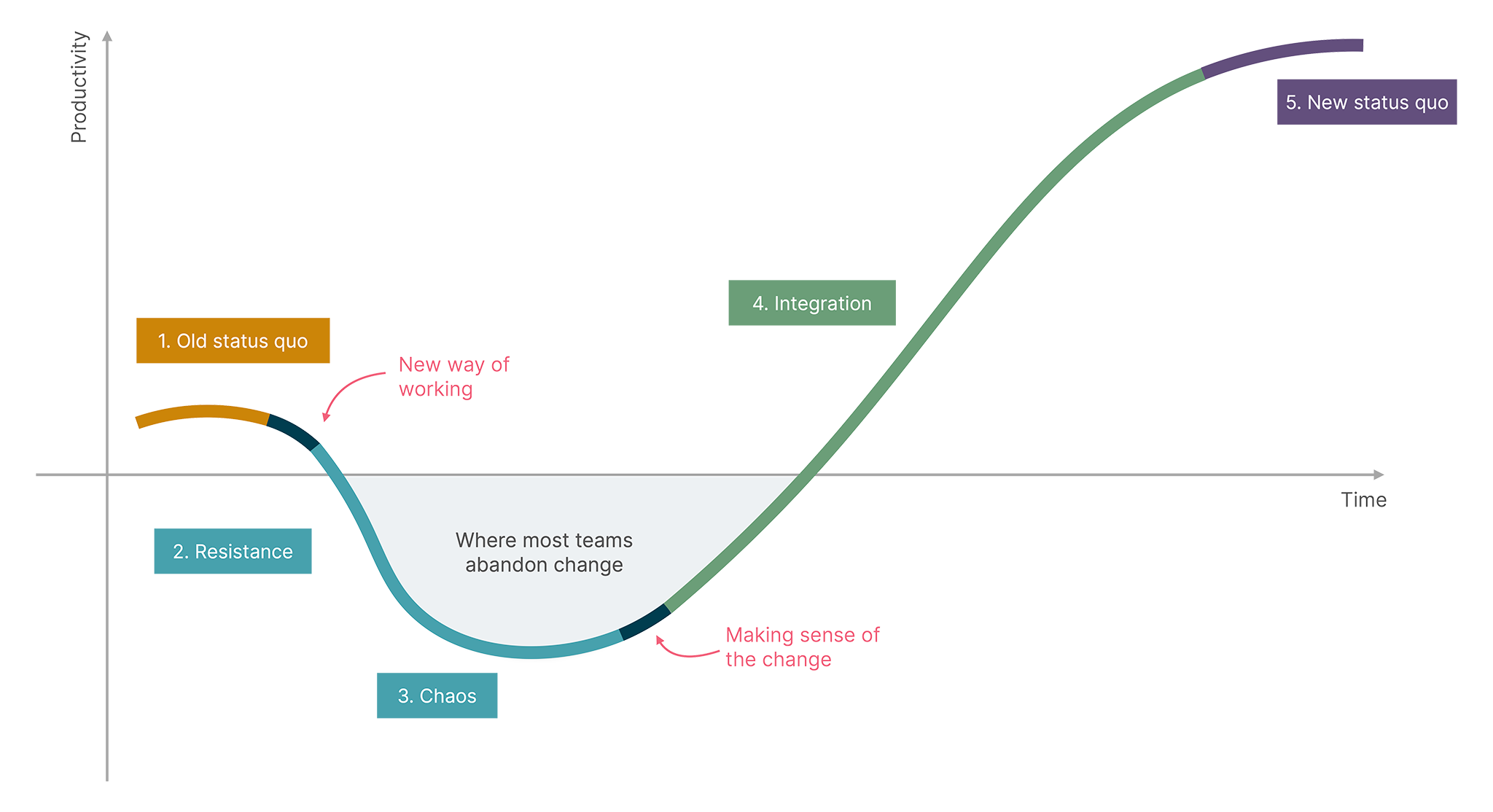

Here’s a hard truth about change. There are no magic bullets. Teams are systems and after a spell of being together, they build an equilibrium. Ways of working, good, bad or ugly, are part of that equilibrium. Every change will disrupt that equilibrium and a period of chaos will ensue. Velocity will invariably take a hit. If you don’t plan for this period of chaos, you’ll overweight the status quo compared to the change. Often, this is where the team abandons changes.

Virginia Satir's process of change

If you’re serious about change, you must buy your team some slack so they can make sense of the change and adopt these new ways of working. Virginia Satir’s change curve, above, illustrates this process. Oh, and if velocity can’t take a hit, don’t bother with change. Your team can do without the stress of futile efforts.

Problematise the normal

Dan Heath talks about a problem called “inattention blindness”. He explains this as a phenomenon where you get so focussed on one task, that you lose peripheral vision. Heck, you’ve got to focus on what you’re doing, under time pressure, so why bother? Sometimes this is a good thing. Like how you may shut yourself out to the white noise of a coffee shop, if you’re also trying to work there.

Inattention blindness can be pernicious when we normalise problems. Heath explains this in the context of sexual harassment in the workplace. In the 60s and 70s, the crime was so acceptable to society that, Heath says, 30% of 2000 companies surveyed in 1960, gave “serious consideration” to “sex appeal” when hiring receptionists and secretaries.

Why do we treat sexual harassment as a crime today? Well, because Lin Farley, a journalist with the New York Times, did the opposite of normalising the problem. Farley problematised the normal by coining the term sexual harassment. She wrote about it. She testified in Congress.

Not everyone of us will lead and act courageously like Lin Farley. Maybe our acts of courage and leadership will be smaller. But we can agree that if you want to problematise the normal, you’ll need slack. Slack allows you to step away from the status quo and examine it from a distance. It allows you to ask the hard questions. If you’re always hammering away at hard deadlines, then good luck problematising the normal.

Bathe yourself in daylight

James Williams, a former Google advertising strategist and now author says that our attention takes three different forms, at three different levels.

🔦Spotlight is the first form of attention that tells us to focus on immediate goals. This is the class you’re tidying up, the user story you must write, the screen you must design or the sprint scope you’ve signed up for.

🌃Starlight is the next level, that enables you to keep track of medium-term goals, such as the next release for your project.

🌞Daylight is the third level. Williams says that at this level we focus on our long-term goals and values. An example of this could be about the team culture you wish to build and the environment you wish to foster in it.

Here’s the rub. Without slack, you lose your sense of perspective. If you and your team are always busy with your spotlight and starlight, you’ll struggle to step back and experience daylight. This affects a variety of team capacities. Williams lists a few - reflection, memory, prediction, leisure, reasoning and goal setting.

Imagine instead, the workplace we can build when each one of us has the mental space to step away from the rigmarole of daily work and view our systems in daylight!

Make sense with pauses

Almost all of us need slack to make sense of our own world. Many of us equate busyness with productivity. They aren’t the same thing. There’s a reason agile teams have retrospectives. It helps the team pause, reflect and make sense of their world. We need more of this, not less. In fact, I believe we must go beyond the structure of the retro, to a more fluid pause.

There’s enough science to suggest that pausing, even letting your mind wander, helps you solve problems creatively. This won’t happen by accident. Definitely not in a distributed world, where Zoom meetings, chat messages and emails fly thick and fast. You must make time for this pause; for your minds, individual and collective, to wander.

In Stolen Focus, Johan Hari passionately advocates for pauses and mind wandering. He quotes Nathan Spreng, professor at McGill University, who attacks a myth about creativity.

“Creativity is not where you create some new thing that’s emerged from your brain. It’s a new association between things that were already there. (Mind wandering) allows more extended trains of thought to unfold, which allows for more associations to be made.”

If creativity needs that space to forge new connections between existing elements, then we must ditch the productivity theatre. We must make time for the pause. Can we give each other the safety to let our minds wander and to disconnect from our devices when we take these pauses? How about we make it ok to say to each other that we were just “thinking” or “doing nothing”?

Do less, achieve more

In a recent podcast (and of course, his book), Greg McKeown provides a deceptively simple approach to build in slack. He recommends following the 85% rule. Greg says that there’s a point after which you get diminishing, even negative returns for your effort. He calls that the 85% point. It’s tempting to give something your 100% or if you believe in hustle culture, maybe even 200%. The fact is that you get most of the value for about 85% of your capacity.

Cole Hechtman tells the story of how Carl Lewis became a champion sprinter not by giving 100%, but by giving 85%. Huh! How? All down to a simple principle - the less we try, the better we do.

Cole Hechtman

“By always striving for 100 percent effort, we try to take on too much. When it comes time to perform, there’s only so much we can focus on or remember at once. If we try to manage every detail, we inevitably get stuck in our heads and tense up.

Instead, when we let go of the idea of perfection and aim just low enough—at around 85 percent effort, we’re able to get out of our own way and let our subconscious self do what we’ve trained it to do. Not only does this make us more effective performers, but it makes our progress more sustainable.”

So how about revisiting the work you do this year, with an 85% lens?

Can you set aside some time each development cycle for your team to reflect on their work?

Can you try not maximising capacity and utilisation when you plan roadmaps and releases?

Can you give yourself the time to pause and think, by just blocking time on your calendar?

The world of work suffers from toxic masculinity. There’s no time to pause. We don’t tire. We’re worthy. We’re mighty. We bite off more than we can chew and then we go through rough spells of epic heroism to drag ourselves out of holes. And then we celebrate the heroes to perpetuate a vicious cycle.

It’s no wonder that we use Slack, the IM tool, to fuel this testosterone fuelled, macho way of working. It’s not a problem with Slack per se, but with the way we approach work.

Alongside that status quo are some sobering facts.

Most of us can’t work deeply for over four hours a day.

Letting your mind wander allows you to make better long-term decisions.

Having time to think improves work performance.

All those facts will tell you we need more slack to work better and be productive. If you read this far in the article, you’ve probably cut yourself some slack already, in an attention poor world. How about extending that slack to your work and to your colleagues? Let 85% be the new 200%!